All summer long a blazing hot pink jolt of marketing buzz for the live-action Barbie movie has electrified the atmosphere. This dynamic energy propelled the film to a groundbreaking achievement: the first female-directed motion picture to soar past the billion-dollar mark in box office earnings! The film’s success goes beyond mere numbers—the Barbie movie breathed new life into the movie theater industry following a pandemic-induced slump.

Of course, Barbie has long been a cultural phenomenon. However, she is not the first doll to revive an industry after an economically catastrophic event.

Be a Doll

In March of 1959, nearly 14 years after Germany’s surrender to the Allied forces and the conclusion of World War II, Barbie made her debut. She emerged as a direct result of the war’s aftermath, with subsequent economic prosperity in the United States and the baby boom positioning the fashion doll for commercial success. However, Barbie’s origins lie with another post-war fashion doll, albeit one targeted at a more mature audience.

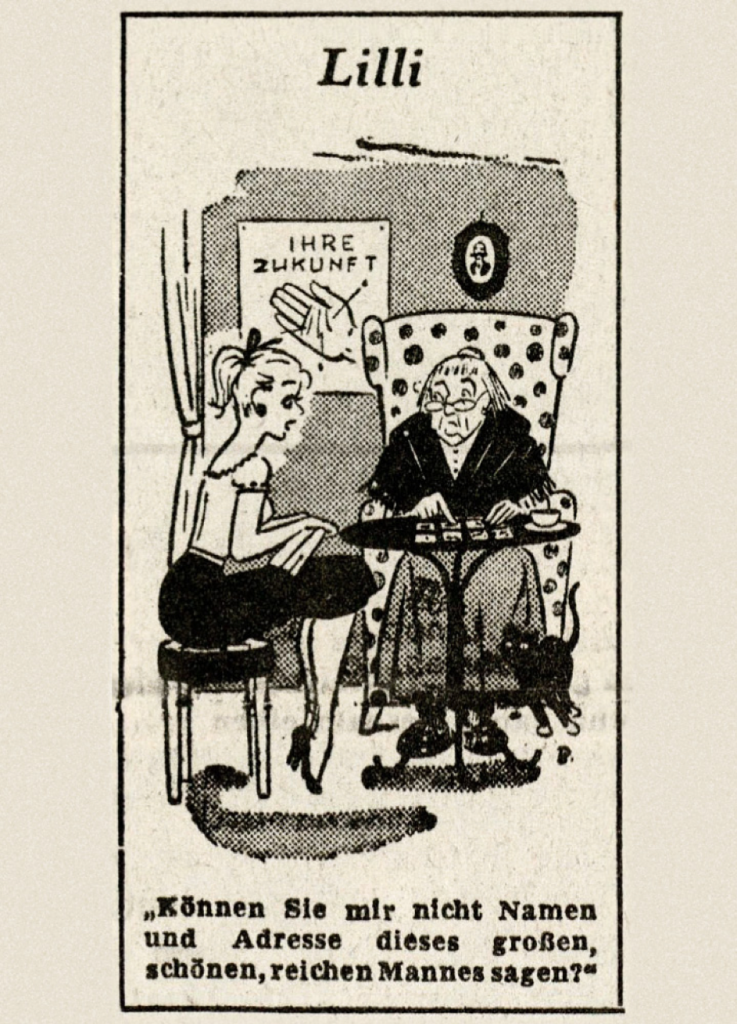

During a visit to Germany, Mattel co-founder Ruth Handler encountered the provocative Lilli doll, an adult novelty toy designed to titillate men with its dress-up and undress features. This encounter sparked Handler’s idea of adapting the same fashion doll concept but aiming it at young girls, instead—a departure from the prevalent baby doll offerings of the time.

Interestingly, the Lilli doll was a comic book character made manifest. In 1945, in war-ravaged and defeated Germany, a man named Axel Springer established a publishing company which would later launch an anti-communist pictorial daily broadsheet called Bild-Zeitung. The inaugural edition showcased a comic strip featuring a provocative blonde named Lilli who captured the post-war zeitgeist. The sexy Lilli became popular enough that she was made into a doll a few years later, the very doll that Ruth Handler encountered in 1956 and which sparked the inspiration for Barbie. In fact, Mattel even purchased the rights to the Bild Lilli doll in the 1960s!

In many ways, Barbie represents the rise of American cultural dominance after Europe was decimated by war.

Théâtre de la Mode

The notion of fashion dolls, dolls designed to wear stylish ensembles, wasn’t entirely novel. In the 16th century, they served as a common method for clothing makers to promote their fashions. This was particularly important since travel to fashion hubs was difficult and mass media to advertise clothing collections did not exist. Thus, miniature dolls clad in the latest styles were dispatched to royal courts to showcase fabric qualities and clothing designs.

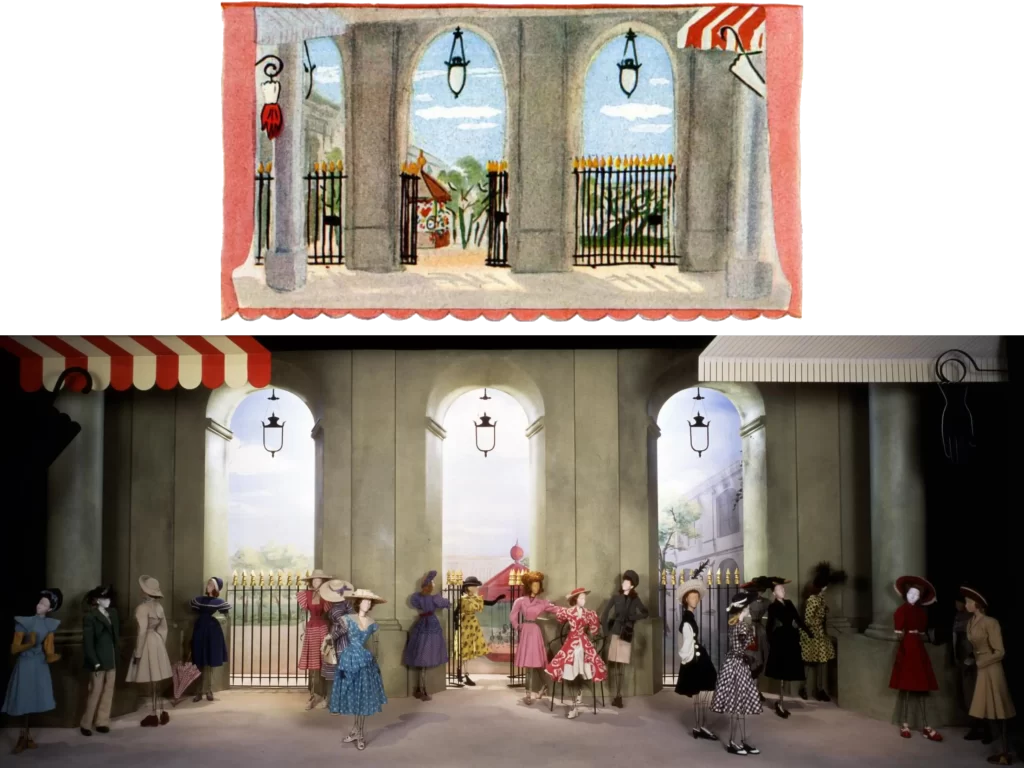

In 1944, this concept found new life after Paris was liberated during World War II. Robert Ricci (son of couturier Nina Ricci) sought to rejuvenate the French fashion industry, which had endured years of hardship under German occupation. Amid ongoing textile scarcities, Ricci and fashion journalist Paul Caldaguès devised a solution: crafting miniature clothes to conserve fabric and adorning dolls with these creations.

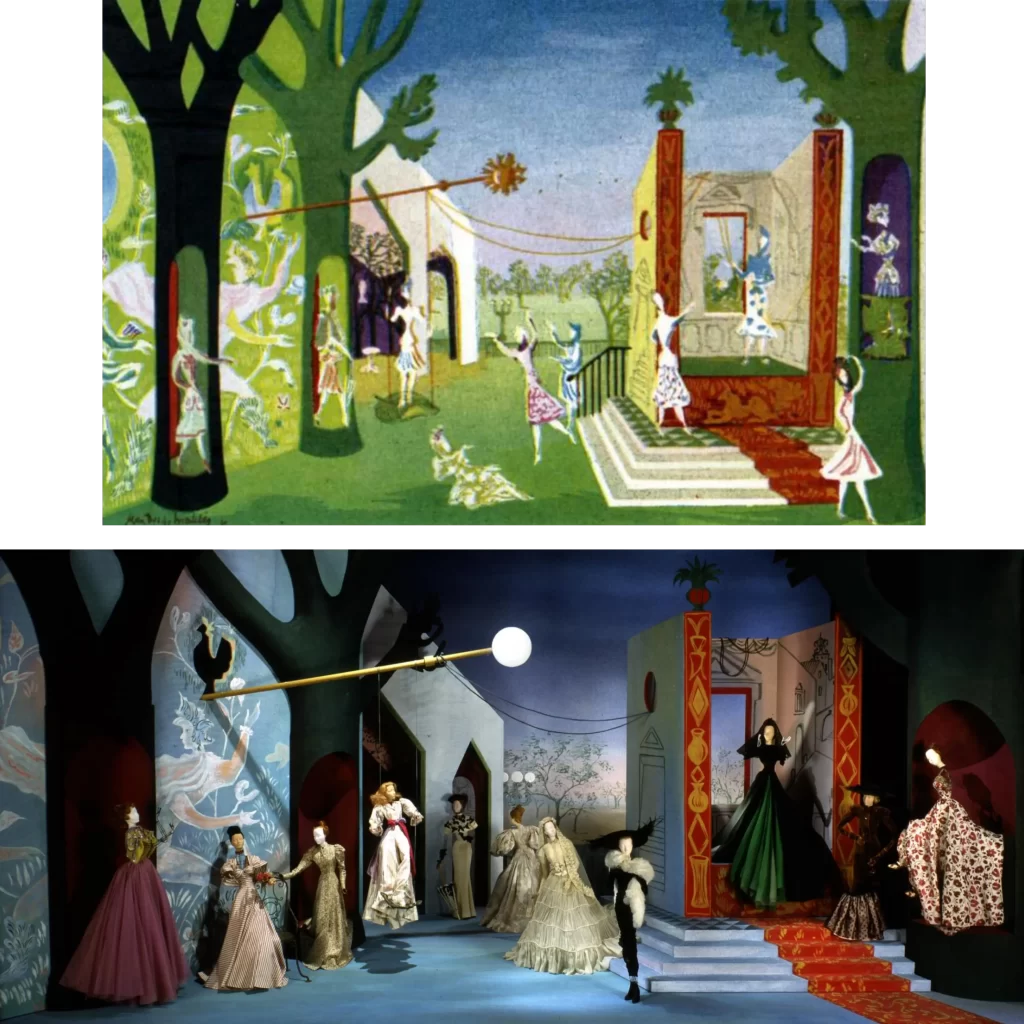

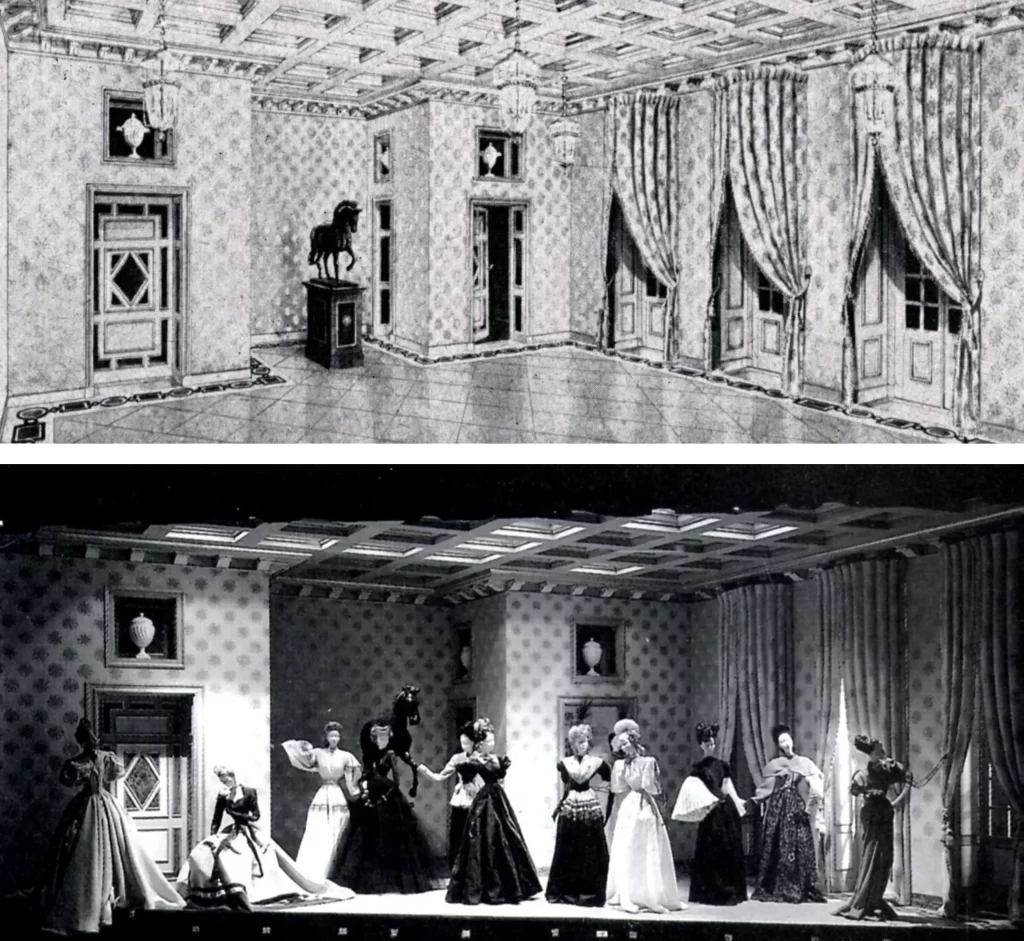

Aided by Lucien Lelong, president of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, Ricci rallied the era’s leading couturiers, including figures like Balenciaga, Balmain, Lanvin, and the house of Hermes. Accompanied by skilled artists and artisans, they embarked on creating the Théâtre de la Mode—an exhibition featuring wire-and-plaster dolls standing 27.5 inches tall, elegantly dressed in couture fashion. Beyond being a visual delight, the exhibition aimed to raise relief funds for war-battered France and offered the couture houses a platform to once again showcase their creativity. Théâtre de la Mode opened in March 1945 at the Louvre and proved a tremendous success!

Setting the Stage

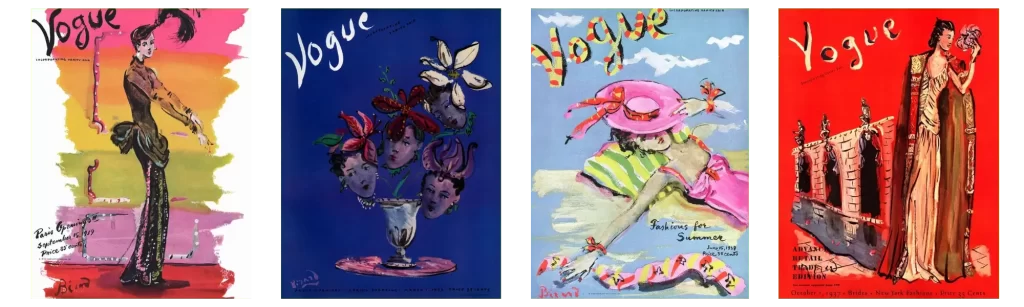

The Théâtre de la Mode showcased top Paris designers and Europe’s notable theatrical and interior designers. Christian Bérard, a painter and scenic designer, served as the project’s artistic director. He was renowned for designing Vogue covers and worked often with the Ballets Russes.

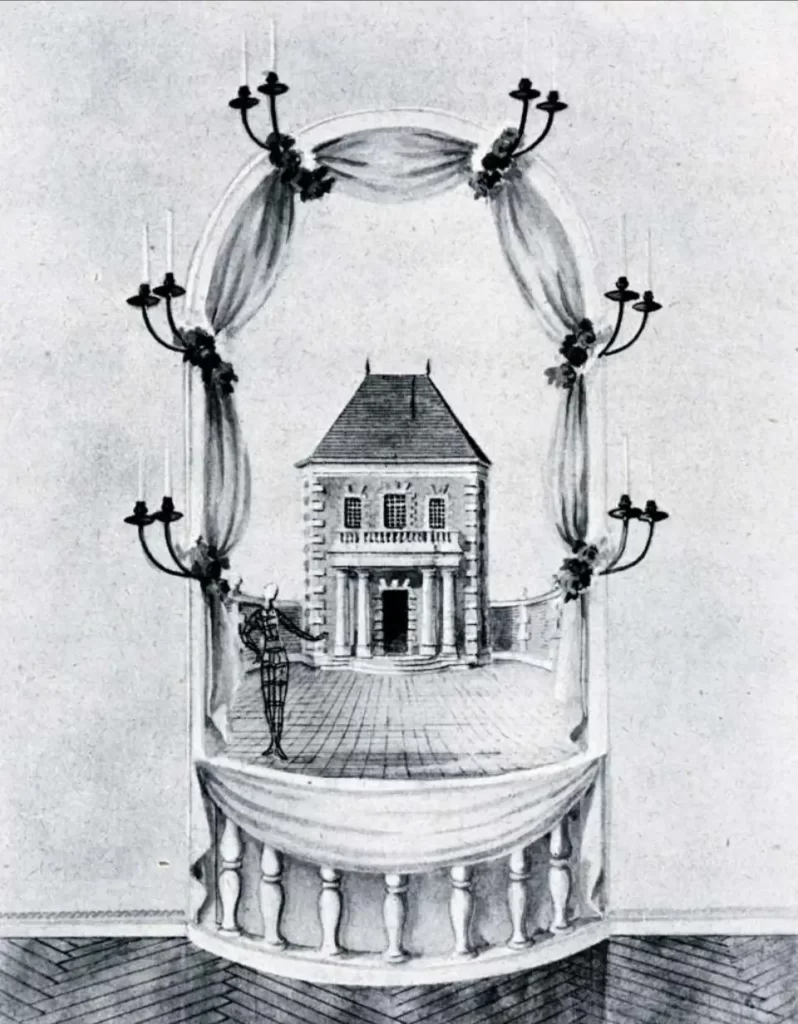

Bérard created his own set featuring a miniature theater with a tiny chandelier in a reference to the larger show itself. However, he also guided a number of high-profile artists and set designers like André Dignimont, Jean-Denis Malclès, and Jean Cocteau.

Cocteau’s tableau is an homage to French filmmaker René Clair’s “I Married a Witch.” It features a large room with bombed out holes that show a peek at the destroyed city of Paris beyond, while a witch on a broom takes flight through the ceiling.

More appropriately for this blog, Georges Geffroy, a renowned 20th-century interior designer crafted a set for the 1945 exhibition. He is one of my own inspirations and I’ve touched on his work previously on this blog here. His “At Home” tableau shows an elegant Parisian apartment in miniature decorated with gold damask and neoclassical motifs.

Unfortunately, this set was among those that did not make it across the Atlantic when the show went stateside. However, Geffroy did get to design the interiors of the actual exhibition hall in New York!

Currently, the Maryhill Museum of Art in Goldendale, Washington displays the Théâtre de la Mode dolls and sets on a rotation of three sets every two years. The museum sits on a cliff over the scenic Columbia River.

Dolls On Tour

So, how did the dolls end up in rural Washington State, of all places?

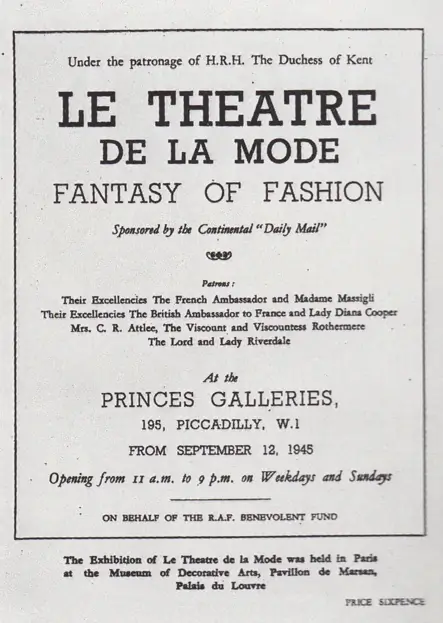

After the Paris success, the exhibition briefly went to Barcelona, then continued its journey to London and Leeds to great fanfare. Later, partial showcases of Théâtre de la Mode were presented in Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Vienna.

Next, the dolls sailed across the Atlantic to New York City with all-new 1946 fashion designs. The De Young Museum in San Francisco hosted the final stop, starting in September 1946. However, after the San Francisco exhibition, the Chambre Syndicale chose not to ship the dolls back to France. At some point, the dolls were placed in the basement of San Francisco’s City of Paris department store, one of the exhibition’s sponsors, and the sets were lost.

The Maryhill Museum of Art eventually acquired the dolls in 1952 thanks to Alma de Bretteville Spreckels, the wife of San Francisco sugar magnate Adolph B. Spreckels and sister-in-law to John D. Spreckels (who donated the California Legion of Honor to San Francisco and the Spreckels Organ Pavilion to San Diego, respectively). She was able to convince Paul Verdier, the president of the City of Paris department store, to donate them to the museum in Washington state where they were displayed for 30 years in relative obscurity, until they were “rediscovered” when sent to Paris in 1983 for restoration. It was in the 1980s, too, that many of the sets were caringly recreated by Anne Surgers from photographs and text descriptions.

And that’s the story of how these important French fashion dolls, symbols or French resistance and resilience during World War II and precursors to fashion dolls like Barbie, ended up in the Pacific Northwest where they can still be seen to this day!