At Maison Dumar Interiors, the aesthetic focus is on translating the design movements of the 17th- through early-20th-century in ways that correspond seamlessly with contemporary lifestyles. Truthfully, this is no short span of time–it covers more than 300 years!

Those 300 years saw the American Revolution that birthed the United States; the French Revolution (itself partially inspired by America’s); the rise and fall of empires; the end of slavery in the Western world; the dawn of industrialization; the development of powered flight; and so on and so forth. Heck, most of our major American cities were founded during this time period. Clearly, a LOT of history occurred between 1600 and 1930! Yet, in the same way that gravity and grand geological processes compress layers of sediment and stone to form strata, history compresses time to give only the most general shorthand for years, decades, and centuries of human history.

When we think of design movements, we often assign them to particular decades. Anyone can recognize the differences between décor in the 1960s versus the 2010s. So why, then, do we expand historical design movements to span entire centuries (or, in keeping with the geological analogy above, compress entire centuries to encompass only one or a few design movements?)?

Well, the answers to such a question are complex, but let’s sum it up to the matter of convenience (see what I did there?). It’s just much easier to lump a bunch of marginally related things together under a uniform label and call it a day! Ergo “traditional design.”

But what is “traditional design,” really? Well, in the broadest sense, one might define it as any interior style that is not “modern.” Then again, what is “modern”?

Historians identify modern history as beginning after the middle ages. In this sense, any interior innovation after the late 15th century could be called “modern.” Hm.

Then again, when we talk about modern design we are usually referencing interiors from the post-industrial 19th century to today. In that case, everything from Thonet bentwood chairs, to highly tufted neo-rococo Victorian sofas, to the sinuous forms of Art Nouveau could be considered “modern.” Well, that doesn’t seem quite right, does it? Maybe “modern” design refers to only post-World War II designs wrought by technological and material innovations that allowed furniture to be highly simplified for even greater mass production?

You now see how complicated it is to define “modern.” How, then, could we possibly expect to define “traditional”? In presuming that there is an established dichotomy between modern and traditional interior designs, and subsequently assigning value judgments to each, we would have to draw a hard line between the two. Let’s draw that line, then.

Let us say for the sake of argument that modern design begins with the Art Deco period and spans to contemporary designs. What can we say about all of the interior styles lumped into this timespan? Well, what most people will pick up on almost immediately is the simplification of designs. For various reasons—some philosophical, others practical—we start to see a significant turn away from ornamentation in architecture and design beginning in the 1920s. As the decades have progressed, designs have become only more reductive, to the point where we see the sterile minimalism of the late 1990s/early 2000s, or the warmer-yet-no-less-minimal styles popular today (a catch-bin of mid-century modern redux, Scandinavian, Wabi Sabi, etc.).

In the background all the while are various social forces that are weighing heavily on design, largely borne of the utopian ideals of detached academicians. For them, there becomes a moralistic impetus to impose asceticism onto architecture and the arts to “level the playing field” and eschew the perceived excesses of profligate elite forbears (Academics really love creating loaded moral conundrums, don’t they?).

So we find ourselves today in a design landscape where everything that is “simple, clean and pure” is exalted as an expression of righteous living, while anything that shows even a modicum of ornament is disparaged as sinful overindulgence. It’s all rather sad, really. And excessively boring!

Yet here we are, which brings us to the question of “traditional” interior design. If modernism has come to espouse youthful priggishness, then “traditional” design is its unholy antagonist. It is, as the kids say, “Boomer.”

That’s not an entirely unfair assessment, either. What most people these days consider to be traditional design is pretty much what one would have found in the moderately-appointed houses of the immediate post-war decades. That’s because inasmuch as there was a counter cultural movement towards the streamlined, there was a much larger mainstream movement towards the comfortable and familiar.

Or rather, the social and economic realities which have molded the tastes of the over-educated, underemployed young consumers of today were not also the realities faced by their parents and grandparents, who grew up instead during a time of expanded prosperity.

As they came of age and opportunity spilled over during the post-war years, Baby Boomers sought all of the trappings that their new prosperity could afford them. They set their sights on the material culture of the elite, who through pedigree and wealth had no trouble acquiring fine historical décor. These historical styles, to which perhaps many a soldier may have been exposed while fighting in Europe, were then distilled into accessible forms to appeal to the popular tastes and wallets of the newly prosperous masses.

And so “traditional design” is born. It is, effectively, an ersatz amalgamation of all of the styles that have risen and crested through history up until World War II. It is at once recognizable, yet nebulous.

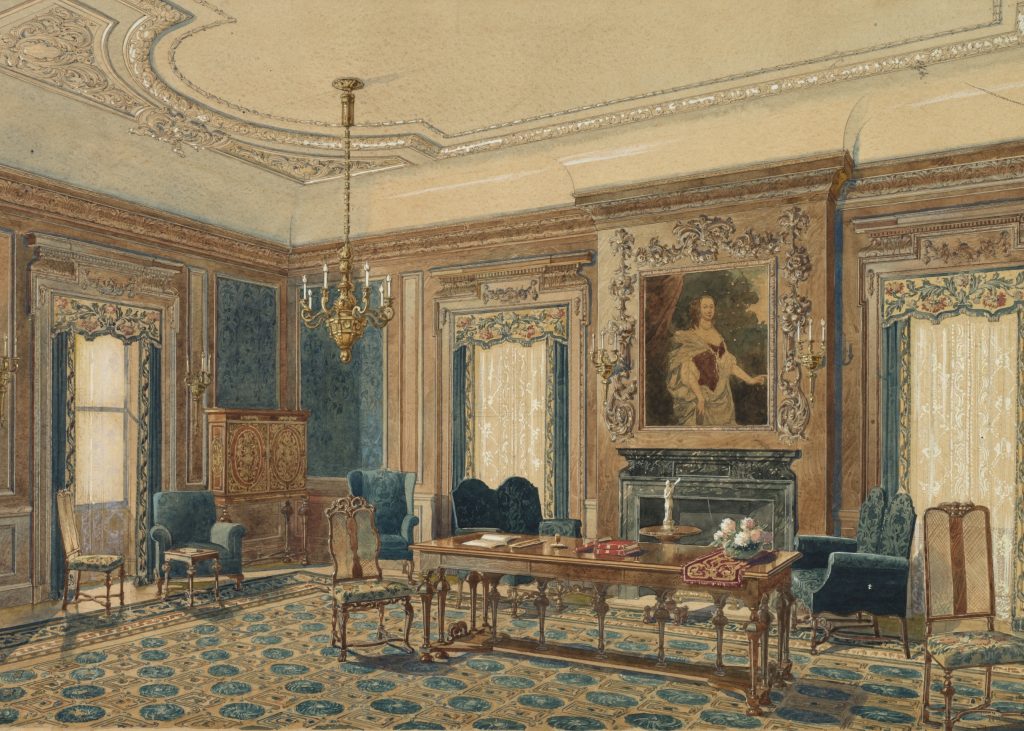

Skirted sofas; ill-proportioned, clunky interpretations of Queen Anne furniture and case goods; heavy wood stains; inoffensive color palettes; etc. We know it well. It is the decor that dressed the un-used sitting rooms (“formal” living rooms, they called it) of the late-20th-century middle class. These mass-market furnishings attempted to emulate, but alas could never duplicate, the beauty and finesse of the masterfully executed designs that only the elite could have afforded in earlier times.

We can finally say, then, that, Yes! there exists a definition for “traditional interior design.” But it should not be confused with the truly spectacular and refined interior styles upon which it may have taken inspiration. “Traditional design” is essentially a compression—a gross oversimplification—of past centuries of unique and diverse design movements enjoyed by the moneyed classes.

When understood this way, the term “traditional” can become pretty irrelevant as a foil to the “modern,” because as traditional design grew in popularity, the moneyed classes purposefully gravitated to less comprehensible styles in an attempt to reinforce social boundaries.

In fact, the unquestioning mainstream embrace of modernism is a relatively recent phenomenon that arose only from the unique historical circumstances of the past 25 years: the advent of the internet; the nihilism of Silicon Valley, with its curmudgeonly start-up culture and championing of upper-middle-class mediocrity; the hyper-inflated elevation of higher education as a pre-requisite for prosperity; the September 11 attacks; the Great Recession; and now the COVID-19 pandemic.

Anyway, as the 20th century drew to a close, the elite turned to minimalism as a means to both ward off attacks from marauding social reformers and also to telegraph their own supposed virtuousness by preaching self-restraint and moderation. Thus, modernism came to be closely associated with the higher social strata and, ut adsolet, percolated down to the newest crop if insecure, impressionable consumers.

It seems then that querulous Millenials and Zoomers are not so much different after all from the elders they love to malign. They have weaponized “Boomer” as an epithet to mean greed and excess, and so anything associated with Baby Boomers comes to be seen as avaricious—including “traditional design.” But in embracing modernism so brazenly, the younger generations are only imitating their social betters in much the same way that the generations before them did. It remains to be seen whether the modern designs of the past century will one day, too, be considered stuffy and “traditional.” Millenials and their younger Zoomer counterparts can only hope that history will treat them kindly. Are they not on the right side of history, after all?

Sadly for them, the existential hand-wringing is for nought. As they try and contort themselves to fit the new, moralized interior framework—manifested as airy white walls, Beni Ourain rugs, the fiddle-leaf fig in a corner, and “thoughtfully curated” spindly stick furniture—the true elite have moved on. They have to keep that pesky middle class at bay, after all, lest they risk bitten ankles.

Those beautifully carved Chippendale chairs are starting to look rather fresh again, these days…

One Response

Comments are closed.