When we think of Chanel today, images of the interlocking double-c logo, tweed jackets, quilted bags with chains, and glass pearls come to mind. These are all style innovations from Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel herself, having been developed over her career in the early 20th century.

However, upon Gabrielle’s death in 1971, the Chanel brand languished for over a decade before being revived by Karl Lagerfeld. It was Lagerfeld who meticulously researched the archive of Mademoiselle Chanel’s designs, particularly from the 1920s and 30’s, to develop the brand code that we associate with the French fashion house today. Yet this shorthand belies the true character of Gabrielle Chanel as a person.

She was a complex and complicated woman whose legacy continues to be both celebrated and denigrated. On one hand, at a time when women’s livelihoods still depended on their husbands, she was an enterprising female entrepreneur who redefined feminine style with simplified and liberating designs. On the other, she was a Nazi sympathizer and traitor to her own country.

While these disparate positions illustrate the status of Chanel’s reputation in our present-day discourses, they do not fully capture her elaborate personality. An approximation of Chanel’s true character might be better gleaned by examining her most personal and intimate spaces.

Origins

It intrigues me to see so many modern women eagerly appropriate hallmarks of Chanel’s look in an attempt to broadcast wealth and status. Of course, Chanel could not have been successful without appealing to the wealthy coterie with which she associated as an adult, but she herself was never of that milieu.

In fact, she was born in 1883 to a traveling salesman father and laundrywoman mother. After the death of her mother 11 years later, Gabrielle and her three sisters were relinquished by their father to the orphanage at the abbey in Aubazines. Needless to say, Chanel’s formative years were marked by austerity and deprivation.

Nevertheless, she was able to leverage the skills and insights she learned at the orphanage to propel herself to better fortune. The simplicity of her personal style, which she would funnel into her fashion business, was a direct product of her impoverished childhood. As a ward of the state, she could never have indulged in the excessive finery that was popular and available to wealthy girls and women at the turn of the 20th century. As she entered society, she could not participate on existing social terms.

Instead, she stuck to what she knew. The uncomplicated clothing she had grown up with was comfortable and allowed a freedom of movement to participate in the sportive activities popular with her upper-class lovers. Having gained entrée into society this way, she exposed the tightly-corseted beau monde women to a new way of life, and it’s difficult to imagine they would not have been envious. After all, girls want to have fun, too, right?

Chanel understood that the wealthy did not necessarily have good taste or judgement. She forsook fashion to develop a personal style rooted deeply in her childhood disadvantages—almost as if on a personal crusade for vindication. And it paid off!

This was the genius of Chanel. She was incredibly subversive! Rather than changing herself to fit into elite society, she made them conform to her. This was a tactic she would use often throughout her career—commandeering the paraphernalia of her own childhood poverty into a precise taste that was uniquely suited for the modern moment. If you can’t join them, beat them!

Still, Chanel was never forthcoming about her background. She was always careful to obscure her humble beginnings and propagated many falsehoods in such service. But the signs were always there, especially when we look at her interiors.

Chanel has been associated with many properties, including a house in the Scottish highlands, an apartment in London’s Mayfair, a flat in Venice, a Norman chateau purchased for her nephew, and a cottage formerly owned by French author Colette. However, only three properties have provided glimpses into Chanel’s interior predilections, and only two of these have been sufficiently documented.

Rue Cambon

The first is the apartment at 31 Rue Cambon, the address which Chanel purchased in 1918 to establish her atelier in Paris.

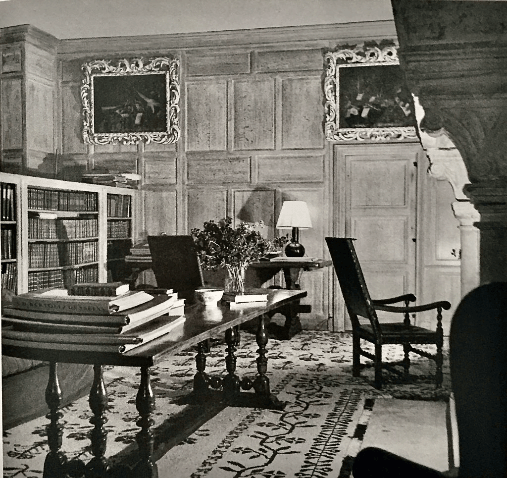

This second-floor apartment was furnished by Chanel and still exists much as she left it in 1971. What is striking about its interior decoration is the richness: varied objects are dispersed throughout the room and volumes of books line the walls. Shades of gold, brown, black, and beige exude a warmth that contrasts with the austere black and white palette so prevalent in Chanel’s fashion designs.

In the main salon, Coromandel lacquer screens flank a deep-seated tawny sofa designed by Chanel herself. We find depictions of various animals—typically in pairs—strewn about, including camels, deer, lions, frogs, and monkeys. Around the apartment, we also find baroque and rococo mirrors and 18th-century-style gilded furniture.

It is said that Chanel was rather superstitious. Sheaves of wheat are displayed near the fireplace, as is a brass wheat sheaf table by Chanel collaborator Robert Goossens. Wheat is meant to symbolize abundance, long life, and Christ. Likewise, the lions mentioned allude to Chanel’s astrological sign, as she was born in August.

The interior architecture of the apartment is not especially noteworthy, making the decor front-and-center. These collected spaces are comfortable and interesting. While the interiors are not necessarily out of place for the gentry of her time, the miscellany does give an impression of a void being filled. This is not surprising, given that Chanel grew up indigent. In many ways, her Rue Cambon apartment reveals an objective to catch up to her new station in life.

La Pausa

While the Parisian Rue Cambon apartment was richly layered and ornate, her next most famous property was just the opposite.

Villa La Pausa is situated on the Côte d’Azur in the French commune of Roquebrune-Cap-Martin between the Principality of Monaco and the French-Italian border. It is so named because its olive groves supposedly served as a rest stop for Mary Magdalene as she fled Jerusalem after the Crucifixion of Christ.

Chanel first came across the property while sailing the Mediterranean with then-lover Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster. She would buy the 5-acre property in the late 1920s and would design the villa herself, with the assistance of architect Robert Streitz.

Unlike the apartment in Paris, Chanel had full control over the architecture of La Pausa, making it an integral part of the interiors. Here, she dug deep into her past and modeled this Mediterranean villa on the austere orphanage where she spent her teenage years. In fact, she specifically sent Streitz to Aubazines to capture its claustral atmosphere.

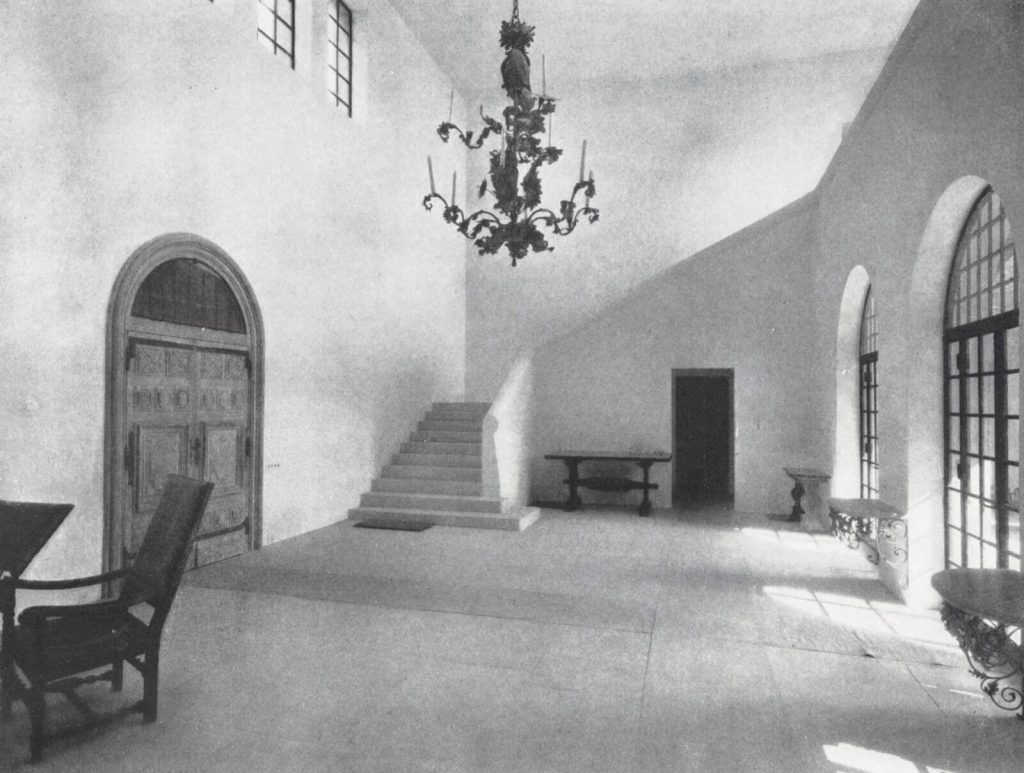

Upon walking into the house through a small entryway, one enters a large double-height grand hall. Here, the central space is flanked by two staircases modeled on the ones used by the monks at the 12th-century Abbaye d’Aubazine.

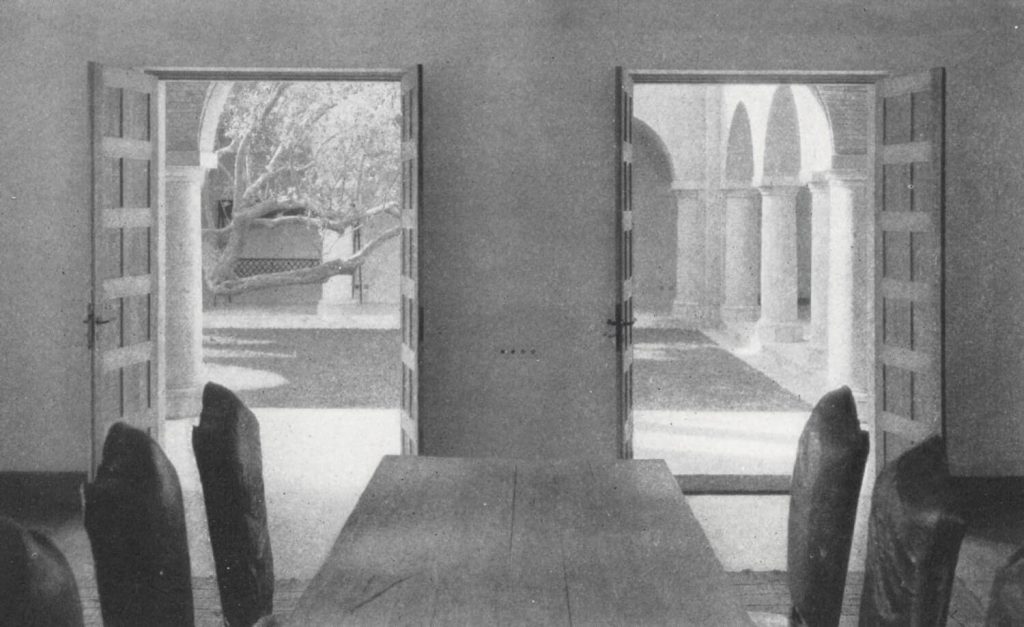

On the back wall, we see further hallmarks of the abbey’s Romanesque architecture by way of arches leading to a cloistered courtyard.

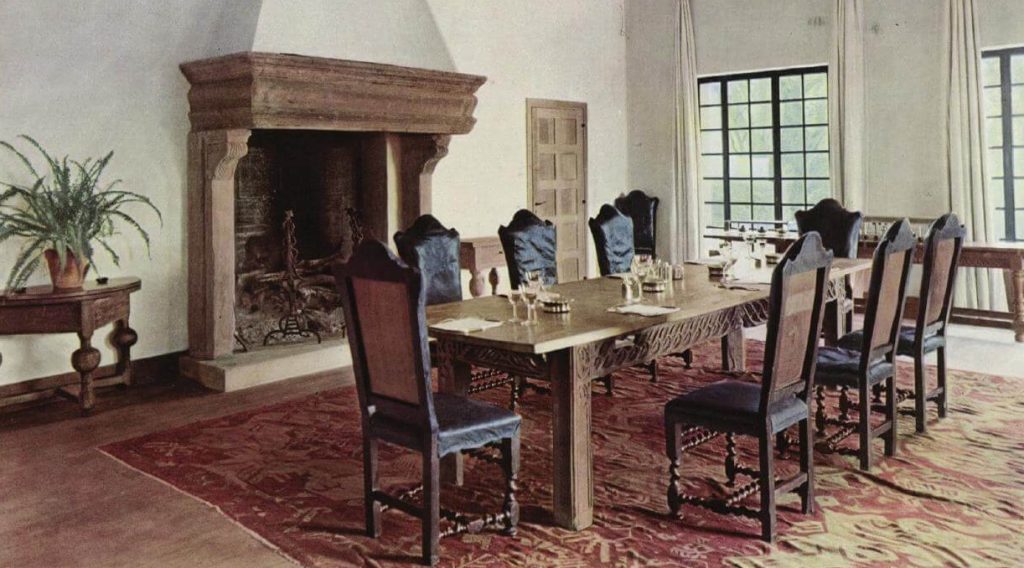

Note that the decor is fairly sparse. Most of the furnishings are of haute époque style and displayed against sparse white walls. The majority of the furnishings were likely donated by the Duke of Westminster himself from England. The rest are of either French Provençal or Spanish origin.

The ascetic simplicity of La Pausa contrasts starkly from the rich indulgence of Rue Cambon. Although Chanel may have been tight-lipped about her origins, the architecture and decor of La Pausa betray her dispossessed childhood. Yet, while guests may have noticed the villa’s contemplative quality, they most likely attributed it to (what they saw as) Chanel’s impeccable taste.

With La Pausa, a property wholly within her control, Chanel sought to subvert the frilly tastes that defined the leisured classes of her time. Even the gardens serve this purpose, planted as they were with rosemary and lavender, which were hitherto seen as “lowly.”

In 1953, La Pausa would be sold to Emery and Wendy Reves, who would redecorate the house to their own tastes with vast collections of art and decorative objects. The architecture, however, would remain largely untouched.

Interestingly, Wendy Reves came from humble beginnings, herself. She was born Wyn-Nelle Russell in rural East Texas in 1916. As she overcame her working-class background, she would adopt the name “Wendy” in adulthood. It only seems fitting that she would take over La Pausa from Chanel.

In the 1980s, after the death of her husband, Wendy Reves would donate their collection of artworks and furnishings to the Dallas Museum of Art, where she specifically requested that the collection be displayed in a scaled recreation of six of the rooms at La Pausa. To this day, one is free to visit the villa’s facsimile at the museum.

The Reveses did not seem to focus their acquisitive attention on furnishings, meaning that the majority of the furniture collections now held by the Dallas Museum of Art in fact belonged to Gabrielle Chanel. That this collection can now be seen here in the United States is quite serendipitous!

Conclusion

Karl Lagerfeld was extremely successful in reviving the House of Chanel after the death of its founder more than 50 years ago by condensing her aesthetic into a recognizable style code. However, this brand DNA does not fully capture the complexity and charisma of Gabrielle Chanel, the person.

While Chanel today may be known as a luxury brand catering to image-conscious customers, it was the tensions of class and privilege that compelled Gabrielle Chanel to stake her own position in society. The unique social circumstances of the early 20th century in turn allowed her to conscript women’s fashion into the modern era.

In fact, it was thanks to Chanel that the modern woman can affect status through fashion. The simplicity of her clothing, along with her selection of materials, did much to flatten the social hierarchy, at least externally.

But status and luxury are about lifestyle, which is much more difficult to affect. Focusing instead on the interior arrangements of the places Chanel lived allows us to get a fuller picture of her complex persona.

The success of Chanel’s business made her an incredibly wealthy woman. There is no question that she could afford to decorate her interiors with the finest objects and furnishings of exquisite craftsmanship. Yet her style was not predicated on the tastes of the privileged people she associated with, but rather on the humble aesthetics of her upbringing.

To some today, she may be remembered as an icon of fashion, but in many respects, she was really an iconoclast.