Historian Arnold Toynbee once lamented the tendency of select colleagues to view “life [as] just one damned thing after another”—a chronological parade of facts with no discernible themes or general movements. On one hand, it is tempting to exercise extreme caution by taking an objective approach and sticking to “just the facts,” eschewing interpretation for fear of arriving at (and promoting) faulty conclusions. But then, history is a human enterprise, and the detection of patterns and development of interpretations is certainly understandable. Advisable, even!

It is the assignment of overarching themes that fosters a coherent understanding of history, after all. As much as a historical record exists, there are still considerable gaps to be filled and tangled webs to be teased apart—or be forever lost to time. It is within these murky areas that the real work of the historian takes place, analyzing the motivations for the products and events of a given age within the context of their zeitgeist.

This work does not come easy, and conclusions can be open to considerable debate; history is continuous. As attractive as the thought of neatly bookended eras may be, in reality ideas, beliefs, and behaviors wax and wane—often concurrently—but may never actually go away. As I have mentioned before, it is extremely convenient to condense history into fathomable eras and periods, but this elides the important subtleties that effect the developmental trajectory of our civilizations. More than a series of defining events, history is truly a series of transitions.

In exploring the development of modern Western civilization, nowhere is historical transition more manifest than in the gardens of Versailles. If its 17th-century formal gardens were constructed to project the power and dominion of man over nature, the late 18th-century Hameau de la Reine was created to re-assert the primacy of nature and its authority over man.

These ideas may seem contradictory, of course, but It is not inconceivable that the latter would arise from the former.

In the 18th-Century, the philosophical outlook of a number of thinkers who advocated a rational re-evaluation of established orthodoxies predominated—the so-called “Age of Reason.“ Nothing was spared this rational treatment: religion; culture; authority, humanity; all were fair game. Nature too, then, was subject to intellectual scrutiny and the organizing abilities of man.

But everything cannot be suspect, and while authority and civilization were ripe for criticism, some philosophers began to seek an “ideal” state of human existence free from the corrupting influence of civilized life.

In France, a group of thinkers developed a theory of economy (an immediate precursor to the classical economics of Adam Smith) called “physiocracy,” which posited that all economic value was derived from the productive efforts of agriculture. To them, the further away a social group was from the productive activity of working the land (read: Nature), the less value they were creating in the economy.

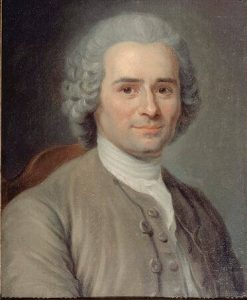

Similarly, Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of the major guiding thinkers of the Enlightenment movement, began to turn to Nature as a moral arbiter.

It was upon these ideals that in 1774 an 18-year-old Marie Antoinette, newly acceded queen of France, directed her architect Richard Mique to renovate the gardens of the Petit Trianon, which she had been gifted by her husband Louis XVI.

Mique set about transforming the gardens of the Petit Trianon in the English style, inspired by the landscape garden at Ermenonville (itself inspired directly by Rousseau’s philosophies). This new style was a direct reaction to the rigidly formal French gardens of before, and sought to imitate the more incidental arrangements one might see in nature. In effect, the landscape garden—first English, then French—idealized nature to create idyllic vistas that reinforced the alleged supremacy of the natural order. It is here, in fact, that one can see the ideals of Enlightenment thought give way to the direct antecedent of the Romantic movement that will flourish in the proceeding century.

A decade later, When Mique began work on the Hameau de la Reine, he planned it as an extension of his earlier English garden. This project, too, was a manifestation of the incipient Romanticism that emerged directly from—and not opposed to—the rationalism that had defined much of the 18th-century.

The concept of a working farm to which the queen could escape the demands of court life was rooted in the values espoused by the Physiocrats and Rousseau’s “cult of Nature.” And so, the Hameau de la Reine came to symbolize the political quandary in which the deeply unpopular queen found herself: desperately trying to ground herself in the perceived morality of the Natural Order while simultaneously appearing haughtily detached from court and country.

Yet the bucolic charm of this little hamlet is unmistakable. With it’s thatch-roofed, half-timbered cottages situated around a small lake, the hameau exudes the pastoral sublimity that would later come to characterize the attitudes and aesthetic fixations of the 19th-century Romantic movement.

In homage, I have created the Hameau de la Reine pillow cover to capture the general spirit of Marie-Antoinette’s magical getaway.

This cover is a counter-part to the Jardin du Roi cover in a clever play on the penchant for asymmetry common in the Rococo style. They will look absolutely splendid displayed together on opposite ends of a sofa!

Like “Jardin du Roi,” the front fabric panel is 100% linen, with a reverse panel in a jacquard weave with a ground of royal “azure” blue featuring a subtle, tonal

rose and dot decoration.

Again, the fresh citron color alludes to the tart sweetness of a citrus confection. Here, the graphic sapphire toile of sapphire depicts a thatched beehive structure, recalling the thatched-roof cottages at the Hameau. The floral and vegetal sprays intimate the taste for such decorations during Marie-Antoinette’s time.

These elements, combined into the “Hameau de la Reine” cushion cover, invoke the charm of the Queen’s hamlet at Versailles, and tell the story of a garden in transition during a changing time. Still, it will bring a bright, beautiful splash of color and texture to any décor scheme.