A few months ago, I was in my local Williams Sonoma store here in Seattle when I overheard a sales associate discussing the virtues of porcelain to a potential customer. Of course, it was clear that this discussion was intended to convince the customer to buy Willams Sonoma tableware but being an avid porcelain admirer, I could not help but eavesdrop.

The associate attempted explaining the history of porcelain, from its East Asian origins to its subsequent manufacture in France. At this point, I decided to interject at the elision of some important history—the fact that Germany was where the creation of porcelain proceeded after Asia.

Anyone familiar with the development of porcelain will know that it was at Meissen, on the outskirts of Dresden, that Augustus II—Elector of Saxony and King of Poland—sponsored the European discovery of hard-paste (true) porcelain fabrication. So coveted was this secret that Meissen would become the standard for porcelain in Europe until it was overtaken by the Sèvres factory later in the 18th-Century after the discovery of kaolin clay deposits in France.

Augustus himself was an interesting, if not altogether savory, character. He was nicknamed “Augustus the Strong” on account of his great physical strength (it is said he liked to demonstrate his strength by bending horseshoes barehanded). He had an indulgent personality with a penchant for excess, which drove him to invest his patronage heavily into the arts and architecture. As a result, the city of Dresden, where he was based, would become a cultural capital.

Among Augustus the Strong’s many obsessions was porcelain, which in the 17th century was produced only in East Asia and amassed a significant premium on import to Europe. Therefore, porcelain collecting became an aristocratic hobby that signaled wealth and status. It’s unsurprising that a man like Augustus would want to amass as large a porcelain collection as possible. The desire to acquire it was so strong that it drove Augustus the Strong to diagnose himself with the “porcelain madness,” for which he blamed his obsession.

Now, while we may write porcelain off today as a commodity due to the cloying pervasiveness of bric-a-brac or the quotidian utility of bathroom fixtures, in centuries past it was so rare as to be considered “white gold”

Even today, some forms of porcelain retain a significant amount of prestige and continue to command high prices in the collector market. In some circles, selecting a China pattern for your wedding registry or buying pieces for entertaining is still very much a habit. It seems that the “porcelain madness” has never truly gone away.

So, then, if one were to purchase porcelain today to appease their own “porcelain madness,” where should one’s attention be directed?

Well, let’s do a little comparison, “March Madness”-style!

United States versus United States

The history of porcelain manufacturing in the United States is a little convoluted, and very few of the legacy producers remain in business to this day, making the collection of American porcelain more difficult.

In the past, Americans would have imported much of their ceramic wares from Europe—especially England. Thus, tracking the early market for porcelain in the US would be no different than tracking the history of porcelain production in Europe.

Interestingly enough, a kaolin clay from North Carolina discovered and used by the Cherokee people played a role in the development of porcelain in England when Josiah Wedgwood commissioned to have five tons of the material shipped to London. Notwithstanding, large-scale manufacturing of porcelain in the United States proper did not occur until the 19th century and did not receive significant market share until the 1900s.

The two largest purveyors of porcelain in the United States that continue to have brand value in the 21st century are Lenox and Mottahedeh. However, neither of these companies manufacture porcelain in the United States today. In fact, Lenox closed its last US factory in 2020 in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even so, both brands continue to offer modern porcelain products at attractive prices for the American market. They also possess some cultural cachet, having both produced dinner services for the White House and other prestigious American institutions.

In terms of trendiness, Mottahedeh’s “Tobacco Leaf” pattern continues to be a favored choice. From a collector’s standpoint, though, I would give an edge to US-produced Lenox wares—particularly from the early 20th century.

Regardless, I find that Mottahedeh’s patterns are altogether much fresher and fit better with today’s lifestyles and aesthetics. Thus, Mottahedeh is the better choice for now.

Winner: Mottahedeh (but only slightly)

(I should note that if you want to purchase truly American-manufactured porcelain today, then Pickard is going to be your best bet.)

China versus Japan

Porcelain originated in China and continues to be produced there in large quantities, with the city of Jingdezhen serving as the heart of porcelain production in that country. For a time, the port at Guangzhou, Guangdong province, served as the only accessible port to foreign traders. Therefore, most Jingdezhen porcelain would be transported to Guangzhou to be finished and subsequently exported to Europe. As a result, much of the exported Chinese porcelain during the 18th and 19th-centuries came to be known as “Canton ware”, Canton being the English name for Guangzhou.

The porcelain industry in Japan began in the 17th century in the town of Arita, which remains the center of porcelain production in Japan. The porcelain wares of Japan were manufactured in Arita and then exported from the nearby port of Imari, and so much of the Japanese exportware came to be called “Imari ware” in the West.

Antique porcelain from both countries has long been popular and still remains highly collectible. However, such popularity has brought a flood of homages, reproductions, and blatant counterfeits into the market, making the collection of Asian porcelains very tricky as an investment strategy. One has to be well-acquainted with a number of subtle authentication techniques to successfully maneuver the market.

Still, from an aesthetic standpoint, you can’t go wrong with either Chinese or Japanese porcelains, so which to choose?

I give the edge to China here, because they are the cradle of porcelain manufacturing and still remain the largest producers of such wares. Their blue and white patterns remain a classic staple of interior decoration to this day, whereas the more superfluous decorations on Japanese Imari can be an acquired taste and have much less visual versatility.

Winner: China

Germany versus France

As discussed above, porcelain as an art form originated in the East. Yet it was in the West where this medium truly reached impressive technical and visual heights!

Even today, the most coveted pieces of antique European porcelain can fetch several hundred thousand dollars on the market, especially if they have royal provenance. It is not uncommon for important collections to reach multi-million-dollar price tags.

When it come to the crème de la crème of European porcelain, one need only know two names: Meissen and Sèvres.

Meissen was the first European manufactory to be established when—in the early 1700s under the tutelage of Augustus II the Strong, mentioned earlier—polymath Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus and alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger cracked the recipe for hard-paste porcelain. With this discovery, Augustus was able to satisfy his obsession for porcelain without having to pay dearly to have it imported from the East, while simultaneously cornering the market for porcelain wares in Europe.

Meissen would become the preeminent purveyor of porcelain until the events of the Seven Years’ War and the discovery of kaolin deposits near Limoges allowed the Sèvres porcelain manufactory to supersede it.

Like Meissen, the Sèvres manufactory was founded under royal patronage. It began as the Manufacture de Vincennes in the 1740s with the support of French king Louis XV and his mistress, the Marquise de Pompadour, as an attempt to compete in the ceramics market in France and abroad. The manufactory was later moved to Sèvres, after which it was purchased outright by the king and was transformed into a conduit of French cultural power with oversight from Madame de Pompadour.

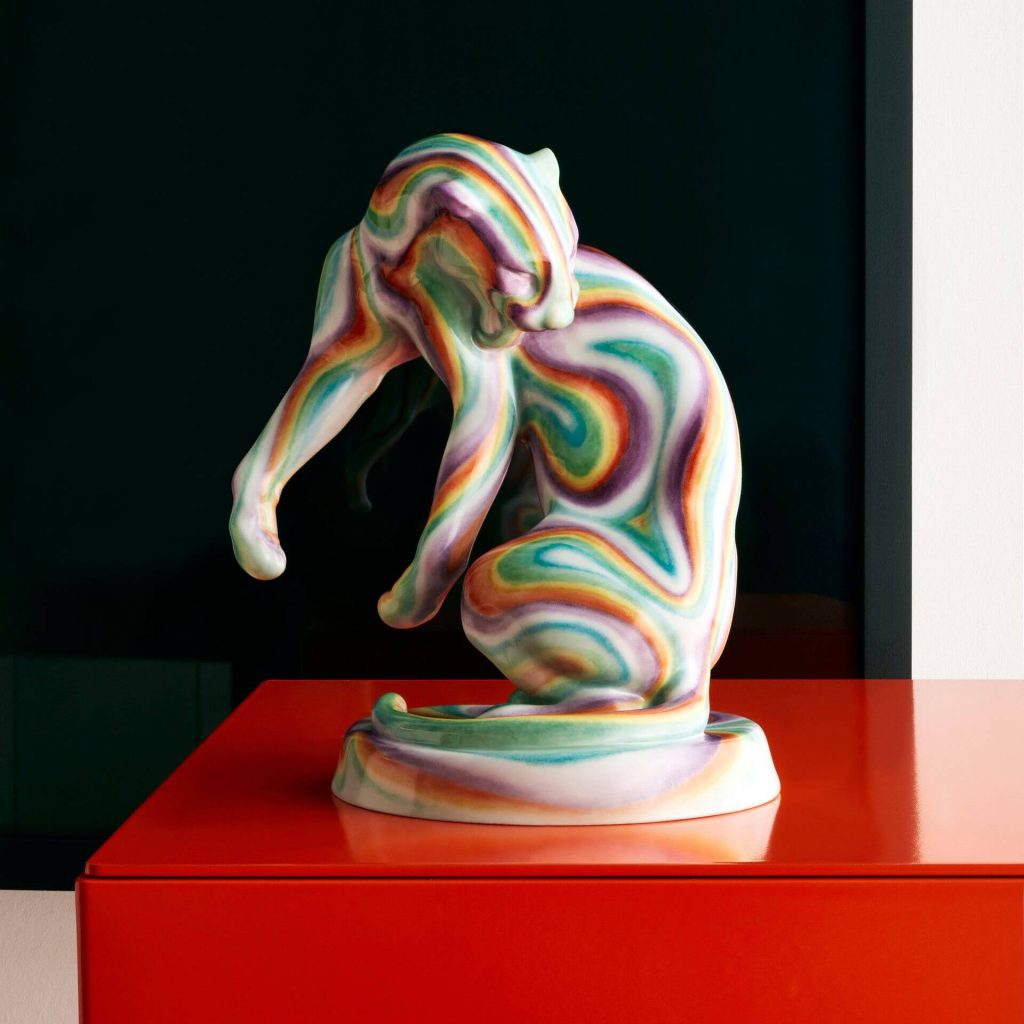

The Meissen and Sèvres manufactories were lauded in the 18th century for their use of porcelain to create beautiful, delicate objects of exquisite artistry. They both continue to produce new pieces to this day in both traditional styles popular in the 1700s, as well as innovative contemporary works for modern tastes.

So, which of these two powerhouses is worthy of your cold, hard cash?

For collectors focusing on antique wares, it might become a wash. Meissen and Sèvres porcelain of aristocratic provenance continues to hold significant value, and collectors are better off focusing on specific styles, timelines, or decorative motifs.

However, if you want to buy new-production pieces, there really is no contest. Meissen remains the most accessible producer, offering multiple opportunities to purchase their porcelain wares at a variety of price points and styles. Meissen can be purchased at any of its boutiques across Germany, in a number of independent retailers across the world, and even online through the Meissen website. Purchasing Meissen porcelain can’t get much easier than that!

Sèvres, on the other hand, continues to distribute pieces more exclusively. New-production Sèvres porcelain can be purchased only at the Sèvres Gallery in Paris, a few international trade shows, or at the showroom at the manufactory and museum in Sèvres, itself. There is no visibility into their pricing and catalogue like there is for Meissen. For Sèvres, then, it may be the case for many that “if you have to ask, you can’t afford it.”

Still, I don’t imagine that Sèvres porcelain would compare unfavorably to Meissen “masterworks,” price-wise. After all, the limited production pieces of today from both manufacturers will likely be the valuable antiques of tomorrow.

Winner: Meissen

Porzellankrankheit

The gift of porcelain–with its luminescent, ringing beauty–has been passed down to us through the ages to serve functional and decorative purposes, alike. It has inspired both greed and perplexity, two sentiments often associated with madness.

Many consumers today may know this material only from being exposed to it through dusty collections of trinkets found at grandma’s house or from being sold for pennies at resale shops, and so can dismiss the “porcelain madness” as a relic of 20th-century middle class pretensions. But the history of porcelain goes back much further and begins in the halls of power and wealth. Today, with younger generations facing increasingly precipitous futures, niche interests like fine porcelain collecting have returned once again to the realm of the privileged.

And yet, access to porcelain has never been greater! The savvy collector can find great rewards with enough knowledge and persistence. Just ask the guy who flipped a $35 yard-sale find into a whopping $700,000 payday!

Yes, the “porcelain madness” of Augustus the Strong is still with us. Happy collecting!

2 Responses

You should mention Vista Alegre of Portugal. It makes Mottahedeh’s better porcelain, including Tobacco Leaf. It also has reproduced a wide variety of other Chinese Export reproduction patterns over the years and some very unusual limited edition pieces, such as a boar’s head soup tureen and a squirrel sauce tureen. In the last decade, they have gone more toward modern and are winning awards for their designs. While not hand-painted like Meissen or Sevres, they are still very impressive, just like Mottahedeh.

Thank you, Ed, for your comment 🙂

Yes, I do love Vista Alegre, too! Their collaboration with Brazilian artist Brunno Jahara is simply divine, and they also have a really great Gryphon pitcher I have my eye on.