I had the pleasure and privilege earlier this fall to travel to the southern United States and visit some of the most important historical house museums in the country. I started my trip in New Orleans and then moved on to Natchez, MS.

Both of these locations are well-known for their high concentrations of buildings that predate the Civil War. Luckily, a few of these buildings have been either restored or preserved as historic house museums. This gives the public a glimpse into the lifestyles and interior decor of a by-gone age.

I did not get the chance to visit every house on my list. This gives me a reason to go back and see more! The houses that I did visit, however, were fine examples of early Victorian interior design in the United States.

This and future posts will focus on showing images that I took of the historic house museums that I visited in what became the Confederacy in the 19th century. I will highlight the splendors and even the sins of Victorian interior life in the antebellum South.

The first post will highlight the Gallier House in New Orleans. This house inspired Anne Rice and currently appears in the new “Interview With a Vampire” series on AMC. But first, let’s define the Victorian era.

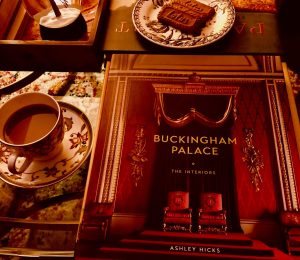

What is the Victorian Era?

The Victorian era begins in 1837 with the accession of Alexandria Victoria to the British throne. It will span for more than 63 years until the death of Queen Victoria in January 1901. She would be the longest reigning monarch of the United Kingdom until Elizabeth II.

This was a time of great social changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution, which was in full swing by the time Victoria acceded the throne. Economic progressed allowed for the creation of a prosperous middle class centered in urban areas, and this concentrated prosperity drew the rural poor into cities.

The United States was not untouched by the Industrial Revolution, which expanded the economic position of the Northern states. New cities were expanding across the country, facilitated by new technologies like the railroad and telegraph.

However, the Northern states would not become the economic engine of the US until after the Civil War. Instead, it was the much more rural American South that was the economic powerhouse of the fledgling country.

The invention of the mechanical cotton gin by Eli Whitney in the late 18th century made cotton a more appealing crop. The discovery of fertile soils in the warm South along the navigable Mississippi River only sweetened the appeal, given that cotton only grows in warm tropical and subtropical climates and requires a lot of water. Couple these with unpaid slave labor and an insatiable demand for cotton products around the world, and you have the makings of an economic miracle.

Cotton made the South rich! So rich, that the desire to show off that wealth followed suit. In no time, wealthy plantation owners were building grand mansions and stuffing them with the most extraordinary things.

But this success was built on the backs of enslaved blacks. Without slaves, the entire system would not be profitable and Southern society of that time would not function. It’s important to keep this in mind as we peek inside these homes.

The Gallier House

The Gallier house is a townhouse located in the French Quarter in New Orleans. It was designed by noted New Orleans architect James Gallier Jr., which moved into the newly constructed home with his family in 1860 on the eve of the Civil War.

Mr. Gallier was not as wealthy as some of the plantation owners or other businessmen residing in New Orleans at the time. Thus, he built his house on one of the less desirable lots, situated next to a small industrial facility. Nevertheless, he built a notable house with many conveniences that were before their time. Additionally, he and his family owned slaves who resided at this house.

In the early 1970s, the Gallier House opened as a historic house museum. This was during a time when historic preservation became fashionable in the United States.

The interiors of the Gallier House were done by Samuel J. Dornsife. Mr. Dornsife was a noted decorator from Philadelphia, and a renowned expert on Victorian interiors. At the Gallier House, his decorative scheme evokes the early Victorian taste of the 1850s.

FRONT OF HOUSE

During the Victorian era, front parlors served as extremely formal reception spaces for great houses. This is the room where a visitor may leave behind their calling card or where the lady of the house entertained company. It is also the room where families celebrated important occasions, like holidays or weddings. As such, these rooms were decorated with the finest a family could afford.

FRONT PARLOR DECOR

Like most formal parlors, the front parlor at the Gallier House is well appointed with period furniture. We can see pieces of Rococo revival furniture, which was extremely popular in the early Victorian era. The Rococo revival hearkens back to the splendors of the Ancien Régime at a time when monarchy was trying to reestablish itself in France. This new Rococo style really started emerging in France under the reign of Louis Phillipe I, the last King of the French.

The gas chandelier, or gasolier, is a central feature of the front parlor. Indoor gas lighting is one of the technological innovations of the 19th century. Notice the intricate plaster medallion.

The front parlor faces onto Royal Street through a pair of handsomely dressed windows. The 19th century can be called the age of the upholsterer because this is when the craft experienced its apogee. Fabric became so affordable that families bought it in numerous yards for decoration. Between the windows sits a pier mirror in the Louis Phillipe style, named so after the last king of France under whose reign the style originated.

Off in a corner, I found this little automaton bird cage. The front parlor has a number of ornaments on display. However, the clutter that is often associated with Victorian design would only come much later in the century.

THE BACK PARLOR

The back parlor sits immediately behind the front parlor through an open passageway. This room was only slightly less formal than the front parlor but was off limits for the unfamiliar visitor. In fact, it was considered a faux pas to step into this room unless expressly invited.

At the Gallier House the back parlor opens up to the courtyard. The bottom sash of the windows reaches the floor, allowing for more air circulation when open. The windows here are also well-dressed, but the painted roller blinds add a casual and whimsical touch.

Another Louis Phillipe-style mirror sits on a central pier behind a marble bust. Beside the marble bust sits a music stand from the French Opera house in New Orleans. James Gallier Jr. designed the French Opera house, which burned down in the early 20th century. The music stand is supposedly the only remnant that remains of the opera house today.

DINING AREA

The dining room is located in the back of the house. As with other public rooms of the house, the dining room here is well-appointed.

The gasolier is believed to be original to the house and can be raised and lowered using the metal tassels. The gondola dining chairs are not of Victorian design, but instead of the earlier Late Neoclassical style (Federal in the United States, Empire in France, and Regency in the United Kingdom). The carpet is richly patterned and exemplifies the habit of installing fitted carpeting in wealthy Victorian households. Bare wooden floors were associated with the lower sorts.

Also, in the back left corner you will see a painting of the Sphinx and an Egyptian pyramid. The Napoleonic campaigns in Egypt at the turn of the 19th century revived an interest in Ancient Egypt.

Immediately off from the dining room, we find a small wash pantry. This is likely a storage room for fine china and crystal used to set the table.

One might also call it the scullery, although it is my understanding that the lady of the house herself would actually wash dishes in this room, as opposed to having her slaves or a scullery maid do the washing. The floor here is a reproduction of kamptulicon, a precursor to linoluem. It was made of cork and rubber and topped with a coat of linseed oil.

UPSTAIRS

Moving to the second floor leads us to a landing that Mr. Gallier used as a study. The space is rather dark due to a lack of windows. However, being an architect, Gallier was quite clever to install a skylight that also opens up as an exhaust vent leading into the attic! Since hot air rises, the vent could be opened up in the summer months to cool down the rest of the house.

The glass vent opens into the attic and there is an actual skylight in the roof above the vent to allow daylight to filter in even in the winter months when the vent is closed.

BEDROOMS

Three bedrooms are accessed right off of the study/landing. The first is the Lady’s bedroom. Mrs. Gallier would use this room as a study, needlepoint, and rest. The floral wallpaper speaks to the feminine nature of this room.

I only managed to photograph the fireplace here. Notice the red coal scuttle in the lower right-hand corner. Coal began replacing wood as an energy and heating source in the United States in the 19th century.

The second bedroom would be the main bedroom where Mr. and Mrs. Gallier would sleep. I didn’t take many photos of this room but did like the gilded French mirror above the fireplace mantle. The wallpaper, too, is of French design and is replicated from a pattern that is also found at the Kelton House Museum in Columbus Ohio. The colors on the wallpaper already show some of the drab colors that will define late Victorian interior design. Notice, too, the gas sconces.

The final bedroom in the main house belonged to the children. The Galliers had four daughters, and all of them would share this single room. The furniture here would be of a lesser quality than the rest of the house, though of better quality than most cheap furniture today.

This room is presented in summer dress, with linen slip covers over the seating and grass mats on the floor in lieu of carpeting. Summer dress is quite common for houses in the South during this time, as the slipcovers are meant to protect the furniture from sweat caused by the stifling summer heat, and the mats made it easier to clean dirt and dust tracked into the house.

SERVICE WING

The final section of the house that I photographed is the service wing, which juts out behind the main house into the courtyard.

Accessible from the main house but still part of the service wing is the bathroom. Being an architect, Gallier was able to experiment a little with his own house and include some comforts that would not have been all too common. Indoor plumbing is one of these comforts, and the Gallier bathroom is pretty remarkable for its advancement. Warm and cool water could be piped into the bathtub, and the bathroom had an indoor flush toilet.

Notice the painted porcelain toilet bowl and the use, again, of kumptulicon.

Although attached to the main house, the second floor of the service wing could only be accessed by going outside onto the covered walkway. This is where we find the slave quarters.

The Galliers had 4 house slaves. They each would have a bedroom leading off sequentially away from the main house. However, slavery would be abolished in the United States only four years after the Galliers moved into the house, and Mrs. Gallier subsequently had paid labor living on the property.

Before the war, the first bedroom would have been occupied by a slave named Laurette, a woman in her 40s. As we can see from the bare walls and sparse furnishings, these were not luxurious accommodations. Especially when we consider the splendors of the main house!

As I touched upon in my blog post about Chanel, simplicity and minimalism in decoration were long considered markers of poverty. In Laurette’s room, the furniture would have been cast-offs from the main house—either broken pieces or things that were no longer fashionable.

Also, although I did not photograph it, the kitchen at the Gallier house is notable for being located inside the house rather than in a separate building. When looking at the service wing image below, the kitchen is the last door on the right. Just above this would have been the bedroom for another slave and, later, the paid servants.

At this time, kitchens were of the open hearth variety and would get extremely hot. The slave bedrooms above the kitchen, one can imagine, would have been unbearable during the summer months.

VISITING THE GALLIER HOUSE

The decor of the Gallier House in New Orleans is a fine example of early Victorian interior design in the United States. It captures the comforts, conveniences, and grandeur of the time just before the Civil War that was predicated on the objectionable institution of slavery.

I highly encourage a visit if you find yourself in the Big Easy. You will find the building at 1126 Royal Street in the French Quarter. You can learn more and book a tour at their website.